Introduction

We've always been interested in the science of coffee here at Dog & Hat.

As we've just completed the SCA Brewing Professional accreditation we thought we'd write a blog series on some of the more important parts that relate to coffee brewing to help you get the most out of the Dialled In Filter Coffee Subscription.

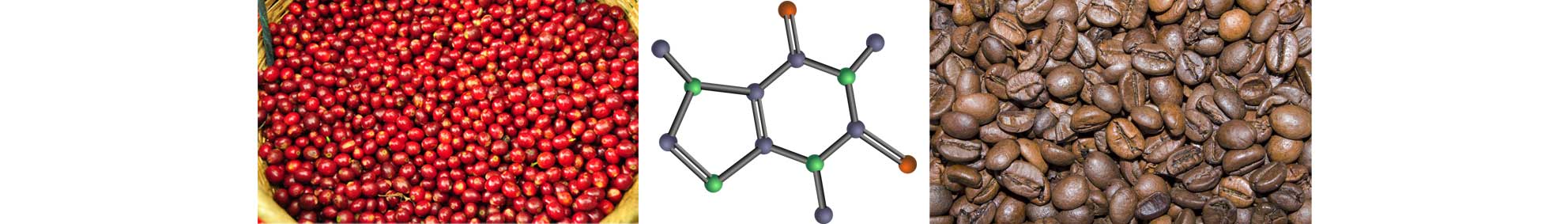

This first part focuses on the science of the coffee bean.

Caffeine and the Art of Coffee Bean Self-Defence

Coffee plants have been cultivated by humans since the 15th century, and have been on this planet for significantly longer than that - so what makes them such great survivors (notwithstanding climate change, which is a threat to us all)?

Well, the coffee plant has a couple of tricks up its sleeve when it comes to dealing with pests that want it for lunch - one is Caffeine and the other is Chlorogenic Acid.

Imagine the scene - you're in the beautiful mountains of Ethiopia and you see a pesky beetle wandering along looking for something to eat, it sees this beautiful coffee flower, heads over to the plant, takes a bite and….. "eurgh!!!!! This is disgusting, I'm not eating that". The coffee plant used the bitterness of the Caffeine and Chlorogenic Acid to defends itself - pretty clever, eh? Interestingly, that's why Robusta is more resilient than Arabica, because it has twice the amount of Caffeine and Chlorogenic Acid in it, making it so bitter that bugs want to go and eat something else, anything else, instead.

Now, another interesting fact about Chlorogenic Acid is that when it goes through the roasting process, it breaks down into two other quite bitter compounds - Caffeic Acid and Quinic Acid... those amongst you that enjoy the odd tipple in the evening will probably be quick to pick up on Quinic Acid, as it is what gives tonic water its distinctive bitter, dry taste in your G&T.

While the bitterness undoubtedly helps to defend the coffee plant against pests, it's not exactly the most sought after taste in a cup of speciality coffee… and if that's all that coffee had to offer, I seriously doubt there'd be a multi-billion pound business around speciality coffee today - although I'm sure there'll always be the need for a big 'ol hit of caffeine in the morning, especially when you have two small, energetic children running around the house.

So what else is in your coffee, and why does it matter?

Other Acids

In addition to Chlorogenic Acid, there are over 30 other organic acids that can be found in coffee - the key ones being Citric, Acetic and Malic.

Citric Acid

When thinking about Citric Acid, try to think about sucking a lemon - not very nice, is it? However, if you combine that lemon with water and sugar you get lemonade… now we're talking - nice, refreshing, lemonade… mmm.

The key is that Citric Acid isn't a bad thing, but when you're making coffee (just as with lemonade) you need to make sure it's balanced with sweetness.

The levels of Citric Acid in your coffee can depend on a number of things - ripeness of the coffee cherry (unripe = more citric), roast level (lighter roast = more citric), and processing.

However, how you brew your coffee can significantly impact the perception of citric acid in your cup.

Acetic Acid

Acetic Acid is essentially vinegar. In high levels it can give a fermented, slightly 'off' characteristic to your coffee, but in small doses it can help give the perception of a 'clean' cup of coffee.

The formation of acetic acid typically occurs during the processing and roasting process (again, lighter roast = more Acetic)

There's not much you can do about it when brewing - the damage has already been done by that point, so make sure you get your coffee from a good farm and a good roaster.

Malic Acid

Malic Acid is really important and is the acid that gives coffee its typical 'fruity' flavour notes. This is because it is also present in large quantities in many fruits - notably apples, and that fools your brain into thinking of fruit when you taste it.

As with Citric Acid, the way you brew can change the perception of the Malic Acid in your cup.

Protein & Carbohydrate

The other key constituents of coffee are amino acids (about 13% of dry mass) and sugars (about 50% of dry mass).

Unfortunately for them, in green coffee, these components lead a pretty solitary, joyless existence, just watching the world go by… but during the roasting process it's party time for the amino acids and sugars… and everyone is invited - this party is called the Maillard Reaction.

During this part of the roasting process (this is the bit before first crack, which is where the water evaporates from the bean and cracks the surface), the amino acids and sugars heat up, pair off and make something magical - the wonderful, flavoursome, aromatic compounds that give coffee its unique and complex taste. These flavour compounds typically take the form of caramel / honey sweetness, nuttiness, etc.

Fats & Oils

Finally, there are the non-soluble parts of the coffee bean that make up the body of your coffee, including fats and organic oils.

Ok, that's great, so now what?

Now you know that your roasted coffee is a primordial soup of bitter, sweet, acidic, caffeine, acids, proteins, sugars, fats and oil... the question becomes - "how does it all come together during the brewing process to provide harmony to my brew?"

Find out more in the next exciting edition of 'Dog & Hat Does Coffee Science'